Each alcoholic drink shaves approximately 30 minutes off the life of a person aged 40 and above, according to a recent study published in the journal BMJ. The comprehensive analysis challenges previous findings suggesting moderate alcohol consumption might be beneficial, instead indicating that any level of drinking poses risks to overall health and longevity.

The study, led by researchers at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, analyzed data from over 40,000 individuals, primarily from the UK Biobank, a large-scale biomedical database and research resource containing in-depth genetic and health information. Participants, aged 40 to 70, provided detailed information about their alcohol consumption habits, lifestyle factors, and medical history. The research team then meticulously correlated these factors with mortality rates over a follow-up period.

“Our results suggest that there’s no safe level of alcohol consumption when it comes to mortality,” stated Dr. Tim Stockwell, one of the lead authors of the study and a scientist at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research. “While previous research has suggested that moderate drinking might have some health benefits, our study, with its robust methodology and large sample size, paints a different picture.”

The study classified participants into several categories based on their average weekly alcohol consumption: abstainers, occasional drinkers (less than one drink per week), light drinkers (one to seven drinks per week), moderate drinkers (seven to 14 drinks per week), heavy drinkers (14 to 21 drinks per week), and very heavy drinkers (more than 21 drinks per week). Researchers found a clear dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption and mortality risk; the more alcohol consumed, the higher the risk of premature death.

Specifically, the analysis estimated that each standard alcoholic drink (defined as 10 grams of pure alcohol, equivalent to a small glass of wine, a can of beer, or a shot of spirits) reduces life expectancy by approximately 30 minutes for individuals aged 40 and older. This calculation takes into account a variety of factors that could influence mortality, including age, sex, smoking status, socioeconomic status, physical activity levels, and pre-existing medical conditions.

The findings challenge the widely held belief that moderate drinking, particularly red wine, is beneficial for cardiovascular health. Previous studies suggesting a protective effect have often been criticized for methodological limitations, such as the “sick quitter” effect, where individuals who abstain from alcohol due to health problems are grouped with lifelong abstainers, skewing the results. The current study attempted to address these limitations by carefully controlling for confounding factors and employing advanced statistical techniques.

The research team emphasized that the 30-minute estimate is an average and that the actual impact of alcohol consumption on an individual’s life expectancy can vary depending on various factors, including genetics, lifestyle, and overall health. However, the study’s overall conclusion is clear: any level of alcohol consumption carries risks, and there is no evidence to support the notion that moderate drinking is beneficial for longevity.

“It’s important to be aware of the potential health risks associated with alcohol consumption, even at moderate levels,” Dr. Stockwell explained. “Our findings suggest that individuals should carefully consider their drinking habits and make informed decisions based on the best available evidence.”

The study’s findings have significant implications for public health policy and individual health choices. They reinforce the need for clear and consistent messaging about the risks of alcohol consumption and support the implementation of evidence-based strategies to reduce alcohol-related harm, such as increasing alcohol taxes, restricting alcohol advertising, and expanding access to alcohol treatment services.

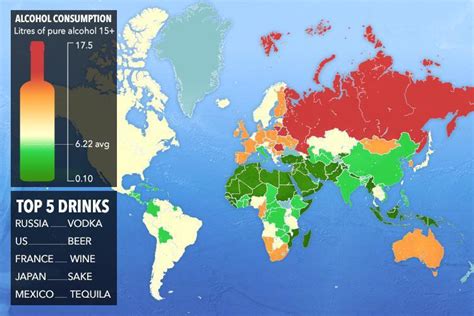

The research team acknowledged that the study has some limitations. The majority of participants were from the UK, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations with different drinking cultures and lifestyle factors. Additionally, the study relied on self-reported data on alcohol consumption, which may be subject to recall bias and underreporting. However, the large sample size, the detailed data on potential confounders, and the rigorous statistical analysis provide strong support for the study’s conclusions.

The study’s findings align with a growing body of evidence highlighting the risks of alcohol consumption. The World Health Organization (WHO) has long recognized alcohol as a leading risk factor for death and disability worldwide, contributing to a wide range of health problems, including liver disease, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and mental health disorders.

Other experts in the field have echoed the study’s conclusions. “This is a well-conducted study that adds to the growing evidence that there is no safe level of alcohol consumption,” said Dr. Sadie Boniface, head of research at the Institute of Alcohol Studies in the UK, who was not involved in the study. “The findings reinforce the importance of reducing alcohol consumption to improve public health.”

The study’s authors hope that their findings will encourage individuals to reassess their relationship with alcohol and make informed decisions about their drinking habits. While abstaining from alcohol is the safest option, reducing consumption, even by a small amount, can have a positive impact on overall health and longevity. The research underscores the need for a more nuanced and evidence-based approach to alcohol consumption guidelines, moving away from the notion that moderate drinking is necessarily harmless or even beneficial.

Further research is needed to explore the specific mechanisms by which alcohol affects mortality risk and to identify potential interventions to mitigate these risks. However, the current study provides compelling evidence that any level of alcohol consumption carries risks and that reducing consumption is likely to improve health and longevity.

The research also touched upon the societal implications of widespread alcohol consumption. The economic burden associated with alcohol-related harm is substantial, encompassing healthcare costs, lost productivity, and law enforcement expenses. By reducing alcohol consumption, societies can alleviate these burdens and improve overall well-being.

The findings of this study should serve as a wake-up call for individuals and policymakers alike. The long-held belief that moderate drinking is harmless or even beneficial needs to be re-evaluated in light of the growing body of evidence highlighting the risks of alcohol consumption. By embracing a more cautious and evidence-based approach to alcohol, we can improve public health and promote healthier, longer lives.

The study also considered the psychological aspects of alcohol consumption. While some individuals may find that alcohol provides temporary relief from stress or anxiety, the long-term effects of alcohol on mental health are often negative. Alcohol can exacerbate existing mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, and can also increase the risk of developing new mental health problems.

Moreover, the study emphasized the importance of considering the context in which alcohol is consumed. Drinking alcohol in moderation in a safe and social setting may have different effects than drinking heavily in isolation. However, the study’s findings suggest that even moderate drinking in a social setting carries risks and that individuals should be mindful of these risks.

The study also highlighted the need for more research on the effects of different types of alcoholic beverages. While some studies have suggested that red wine may have certain health benefits due to its antioxidant content, the current study did not find evidence to support this claim. The researchers emphasized that the risks associated with alcohol consumption are largely independent of the type of alcoholic beverage consumed.

The findings of this study are particularly relevant in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has led to an increase in alcohol consumption in many countries. The pandemic has created a perfect storm of factors that can contribute to increased alcohol consumption, including stress, anxiety, social isolation, and boredom. The study’s findings serve as a reminder of the importance of being mindful of alcohol consumption during this challenging time and of seeking help if you are struggling with alcohol use.

In conclusion, the study provides compelling evidence that any level of alcohol consumption carries risks and that there is no safe level of drinking when it comes to mortality. The findings challenge the widely held belief that moderate drinking is beneficial for health and reinforce the need for clear and consistent messaging about the risks of alcohol consumption. By making informed decisions about their drinking habits, individuals can improve their health and longevity.

Expanded Context and Further Information

The study published in BMJ builds upon decades of research investigating the relationship between alcohol consumption and health outcomes. Early studies often suggested a J-shaped curve, indicating that moderate drinkers had a lower risk of cardiovascular disease and overall mortality compared to both abstainers and heavy drinkers. However, as research methodologies have improved and larger, more comprehensive studies have been conducted, the evidence supporting the J-shaped curve has weakened.

One of the key challenges in studying the effects of alcohol consumption is accounting for confounding factors. Individuals who abstain from alcohol may do so because they have underlying health problems, which can skew the results of studies that compare abstainers to moderate drinkers. The “sick quitter” effect, as mentioned earlier, is a prime example of this bias.

Another challenge is accurately measuring alcohol consumption. Self-reported data, which is commonly used in epidemiological studies, is subject to recall bias and underreporting. Individuals may underestimate how much alcohol they consume, either intentionally or unintentionally.

The BMJ study addressed these challenges by using a large sample size, detailed data on potential confounders, and rigorous statistical analysis. The researchers also used a variety of sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of their findings.

The study’s findings are consistent with the recommendations of many health organizations, including the WHO, which advises that there is no safe level of alcohol consumption. The WHO recommends that individuals who choose to drink alcohol should do so in moderation and be aware of the potential risks.

The study’s findings also have implications for alcohol policies. Many countries have guidelines on safe drinking limits, but these guidelines vary widely. Some countries recommend lower limits than others, and some countries do not have any guidelines at all.

The study’s findings suggest that countries should consider lowering their recommended drinking limits and implementing policies to reduce alcohol consumption. These policies could include increasing alcohol taxes, restricting alcohol advertising, and expanding access to alcohol treatment services.

The study’s findings are not intended to be alarmist, but rather to provide individuals with the best available evidence so that they can make informed decisions about their drinking habits. The researchers emphasized that abstaining from alcohol is the safest option, but that reducing consumption, even by a small amount, can have a positive impact on health and longevity.

It is important to note that the effects of alcohol consumption can vary depending on individual factors, such as age, sex, genetics, and overall health. Individuals who have certain medical conditions, such as liver disease or heart disease, may be more susceptible to the harmful effects of alcohol.

Individuals who are concerned about their alcohol consumption should talk to their doctor. A doctor can assess their risk factors and provide personalized advice on how to reduce their alcohol consumption.

The study’s findings are a reminder that alcohol is a powerful substance that can have both positive and negative effects on health. By being mindful of their drinking habits and making informed decisions about alcohol consumption, individuals can improve their health and longevity.

The study also highlights the importance of promoting healthy lifestyles in general. Eating a healthy diet, getting regular exercise, and avoiding smoking are all important for maintaining good health. These healthy habits can help to offset the negative effects of alcohol consumption.

Finally, the study emphasizes the need for more research on the effects of alcohol consumption. There are still many unanswered questions about the relationship between alcohol and health. More research is needed to identify the specific mechanisms by which alcohol affects mortality risk and to develop effective interventions to reduce alcohol-related harm.

FAQ: Alcohol Consumption and Longevity

1. Does this study mean that I will definitely lose 30 minutes of my life for every alcoholic drink I consume?

No, the 30-minute figure is an average estimate based on the study’s analysis of a large population. The actual impact of each drink on an individual’s life expectancy will vary depending on a range of factors, including age, sex, genetics, overall health, lifestyle choices (such as smoking and exercise), and drinking patterns (frequency and quantity). The study highlights a statistical correlation but cannot predict the exact outcome for any single person.

2. I’ve heard that red wine is good for my heart. Does this study disprove that?

This study casts doubt on previous findings suggesting that moderate drinking, including red wine, provides cardiovascular benefits. The study found no evidence to support the notion that any level of alcohol consumption is beneficial for longevity. While red wine contains antioxidants, the risks associated with the alcohol itself appear to outweigh any potential benefits. Other healthier ways to promote cardiovascular health include regular exercise, a balanced diet, and maintaining a healthy weight.

3. If moderate drinking is so bad, why have doctors previously suggested it might be okay?

Earlier studies suggesting potential benefits of moderate drinking have been criticized for methodological limitations, such as the “sick quitter” effect, where individuals who abstain from alcohol due to health problems are grouped with lifelong abstainers, skewing the results. This study attempted to address these limitations by carefully controlling for confounding factors and employing advanced statistical techniques. The current research, with its larger sample size and rigorous analysis, provides stronger evidence against the idea of a “safe” level of alcohol consumption.

4. What if I only drink on weekends? Does that make a difference?

The study focused on average weekly alcohol consumption rather than specific drinking patterns. While the study didn’t specifically address the impact of binge drinking versus spreading out alcohol consumption throughout the week, other research suggests that binge drinking can be particularly harmful. Consuming a large amount of alcohol in a short period of time can increase the risk of alcohol poisoning, liver damage, and other health problems. It’s important to consider both the quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption.

5. What should I do with this information? Should I stop drinking alcohol altogether?

The study’s findings are intended to provide individuals with the best available evidence so that they can make informed decisions about their drinking habits. Abstaining from alcohol is the safest option, but reducing consumption, even by a small amount, can have a positive impact on health and longevity. If you are concerned about your alcohol consumption or have questions about how to reduce your drinking, you should talk to your doctor. They can assess your risk factors and provide personalized advice. The study does not explicitly demand abstention, but rather advocates for informed choices based on the risks involved with any level of alcohol intake.